1. Open Data in Healthcare: Definition and Current Status

Open Data means making data usable for everyone. In healthcare, this means providing aggregated and anonymized health information for public access. The goal: foster research, improve care, and drive innovation (European Commission, 2024).

Two criteria are key:

- Free availability

- Machine-readable formats for reusability

Personal health data is excluded and strictly protected. Open health data is usually aggregated, such as epidemiological statistics.

The EU has been driving standardization and cross-border exchange through the European Health Data Space (EHDS) since 2024 (European Commission, 2024). In Germany, the Health Data Use Act (GDNG) supports Open Data (Federal Ministry of Health, 2025).

2. GDNG and ePA: The Legal Framework

GDNG – Health Data Use Act

The GDNG has facilitated secondary use of health data for research and public purposes since 2024. It established the Health Research Data Center at BfArM as the central access point for data and defined strict data protection requirements (BfArM, 2025).

ePA – Electronic Patient Record

Since January 2025, all statutory health insurance members automatically receive an ePA. It allows individuals to share data on their own terms. This model strengthens data sovereignty and provides a foundation for connected healthcare (Federal Ministry of Health, 2025).

Both instruments create the basis for a responsible Open Data culture.

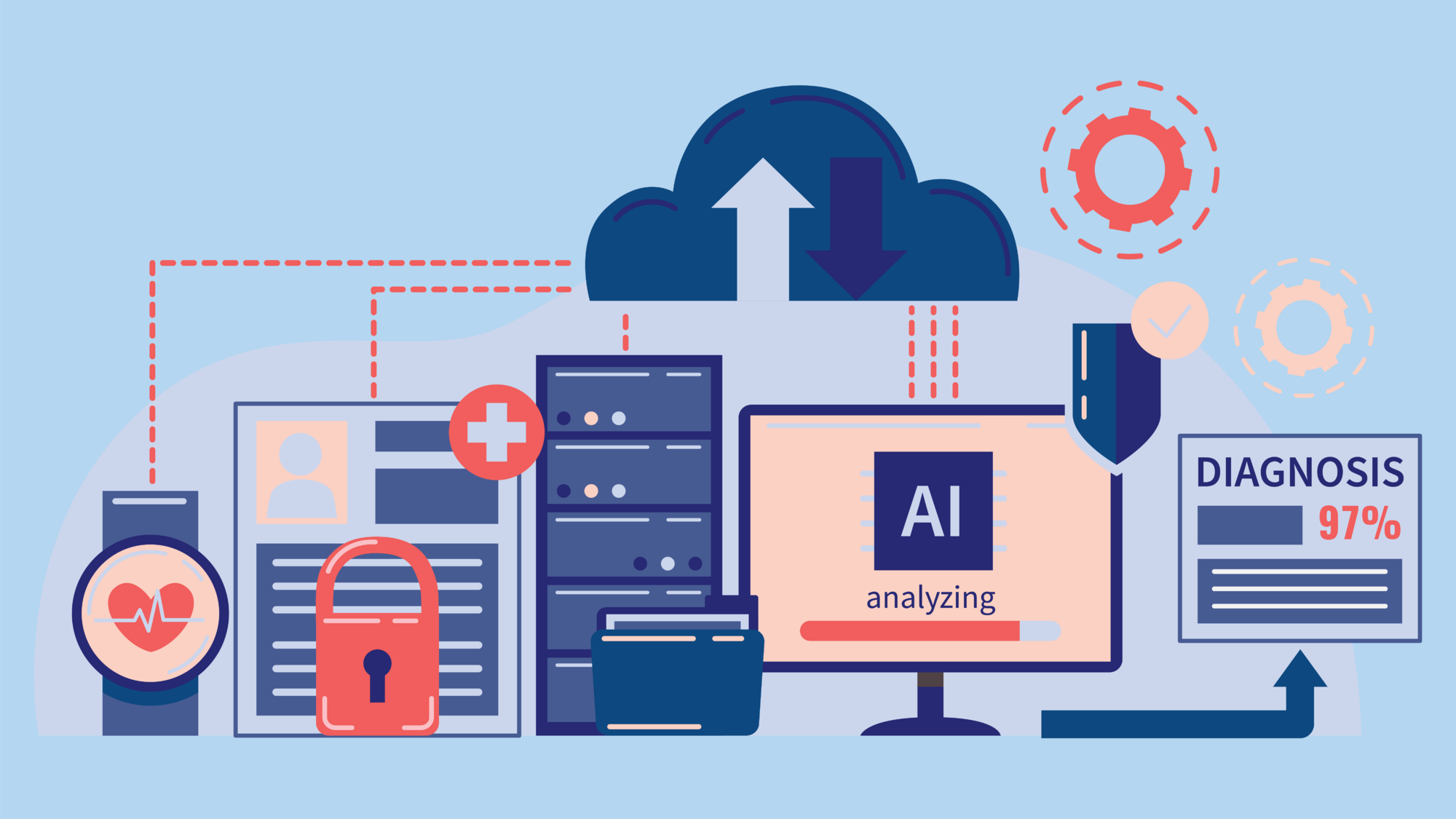

3. Technical Foundations: Interoperability, Standards, and FAIR Principles

The biggest challenge for Open Data is lack of interoperability. Data resides in silos, and formats vary. The solution: standards.

- FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources): Open standard for data exchange in healthcare (HL7 International, 2025).

- OMOP Common Data Model: Harmonizes clinical data for research and AI (OHDSI, 2025).

- Terminologies: LOINC (lab data), SNOMED CT (clinical terms) ensure semantic consistency.

Open Data infrastructures should also follow FAIR principles (OECD, 2024):

- Findable: Data must be discoverable.

- Accessible: Access under clearly defined conditions.

- Interoperable: Use of standards.

- Reusable: Reusable formats and open licenses.

Open-source tools like Synthea or OMOP ETL frameworks enable practical implementations.

4. Research, Prevention, and Care Through Open Data

Open Data can:

- Improve early warning systems for epidemics.

- Promote personalized medicine.

- Highlight care gaps.

Example: During COVID-19, dashboards from the RKI and EU Open Data portals provided real-time infection data. Today, open registries for cancer, diabetes, or heart disease can accelerate preventive strategies.

5. Data Protection, Ethics, and Data Sovereignty

Open Data does not end with technical access. Trust is essential. Key elements include:

- Pseudonymization instead of anonymization to preserve research value.

- Strict access controls at the Health Research Data Center.

- Ethics committees for AI projects.

Ethical questions remain: How do we prevent algorithmic bias? How do we protect minority groups from misuse? Bias audits and clear governance structures provide answers (OECD, 2024).

6. Practical Examples: Initiatives, Tools, and Applications

- EHDS: Promotes secure data exchange in Europe (European Commission, 2024).

- Health Research Data Center: Central access for research in Germany (BfArM, 2025).

- NFDI4Health: Network for research data infrastructures.

- Tools: OpenEHR, Synthea (synthetic patient data), OMOP CDM (OHDSI, 2025).

Hospitals use these approaches for AI-driven diagnostics, while startups develop digital therapies. Example: Projects like NUM-CodeX leverage OMOP and FHIR for research data integration.

7. Conclusion and Outlook

Open Data is no longer a future concept but a reality—with enormous potential for research and care. However, it requires standards, clear legal frameworks, and ethical guidelines.

With EHDS, GDNG, and ePA, the framework is emerging to make healthcare systems smarter. The vision: data-driven prevention, personalized therapy, resilient health systems.

Those who invest in interoperability, data literacy, and open structures now will shape the medicine of tomorrow.

The contents of this article reflect the current scientific status at the time of publication and were written to the best of our knowledge. Nevertheless, the article does not replace medical advice and diagnosis. If you have any questions, consult your general practitioner.

Originally published on